02 Oct Noelle Viñas

When did you write your first play? What was it about & how do you feel about it now?

Oh boy. I wrote my first play at 12 or 13 years old about the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention, and if memory serves I had to present it at some type of school-wide history fair in the cafeteria (?!) with my partner Hannah. While I was excited about the history of women’s rights at the time, I knew then (and am even more certain now) that it was a boring play. I wasn’t activating those outrageous female characters from history well enough. I remember thinking Alice Paul was a rockstar and wanted to portray her as one, but didn’t think I’d be allowed to do that since the 1848 convention was before she was born. Now I think anachronism be damned, I should’ve done it.

Do you have an established writing process or do you approach each project differently?

Every project is different, because plays take different forms: my climate-change-penguin-god-play requires poetry and recording my dreams first thing in the morning, but Derecho was built out of listening to dialogue of people similar to my family living in an adjacent reality. One common denominator for every play I’ve ever written is that there’s always a hot-mess-draft first phase (my phrasing), where I get absolutely everything down on paper: poetry, monologue, unrealistic world-building, etc — everything out of me before I can really start working on what the play actually is. Almost every single time, my hot-mess-draft is changed radically, but little archival bits of it stay in the final version, and I often find my way back to those original impulses. Beating a play out in an outline only works for me after I’ve written that crazy, nonsensical first draft. If I write the outline before the hot-mess-draft, the play is dead in the water.

What has been your most ambitious undertaking as an artist?

Moving to San Francisco, a city I’d never lived in beforehand, with the dream of producing my play Apocalypse, Please and actually doing it in less than two years is definitely up there. It really taught me how to get to know a theater scene in virtually no time and how to collaborate fruitfully with people you are just getting to know. It was a joyful success that formed lasting collaborations and learning experiences that flourish to this day and changed my DNA as an artist/human (I’m marrying my main collaborator!). It also taught me that I should probably not produce, direct, and write a play all at the same time ever again.

Which other playwrights have inspired you?

I know everyone’s sick of Tennessee Williams, but my mom’s a high school English teacher who used to histrionically read his monologues every time I had an audition as a teenager, so I’ll never escape his legacy. I also think there’s something rich and sexy about Williams that lends itself to the matrydom that Latinas like my mom love. Maria Irene Fornes has a hidden logic I can always get behind, Benjamin Benne’s use of language really excites me, and Guillermo Calderon’s plays (in the original Spanish) are both incisive and concise, something I dream of one day being. Right now I’m reading a lot of Julia Jarcho, who messes with an audience in exhilarating ways.

What is your favorite play written by another playwright?

Lorraine Hansberry’s Raisin in the Sun continues to be one of the most subversive plays in the canon while also being so true to life. I love it every time I re-read it.

How has Playwrights Foundation’s Resident Playwrights Initiative helped you?

It has given me an artistic home, resources to workshop new work while taking up space as a playwright, and has been a place to come to when I’m in crisis and in celebration. In short, I don’t think I would’ve had the courage to leave a full-time job and become the writer I am today if it weren’t for the Resident Playwrights Initiative. And in that intervening time, my writing got better because it was given the resources to be more focused.

What was your catalyst for writing Derecho?

First, feelings of strangeness in what I thought was my understanding of my Latin-American community in Virginia before coming home from college and the reality once I was actually home for the summer. And secondly, the “hispandering” that often comes from our elected officials – sometimes it is purposeful and honest, and other times it assumes we’re a monolith that we will never be. My ongoing frustration of Latinx plays and people all being painted with the same brush (when we are really so many different languages, colors, and countries), really pushed me to try to take a cross-section of how different we can be when it comes to our aspirations and values.

What are you hoping to learn from Derecho appearing in the Rough Reading Series?

I hope to learn more about how white supremacy can rear its head in communities of color – and I really hope to take a look at the structure of my barrio moments (you’ll see what those are if you come!) and see how they work in different readings from night-to-night.

What do you want audiences to take away from your work?

Even the things you know deep down can become unknown to you if you spend enough time trying to please other people.

________________________________________

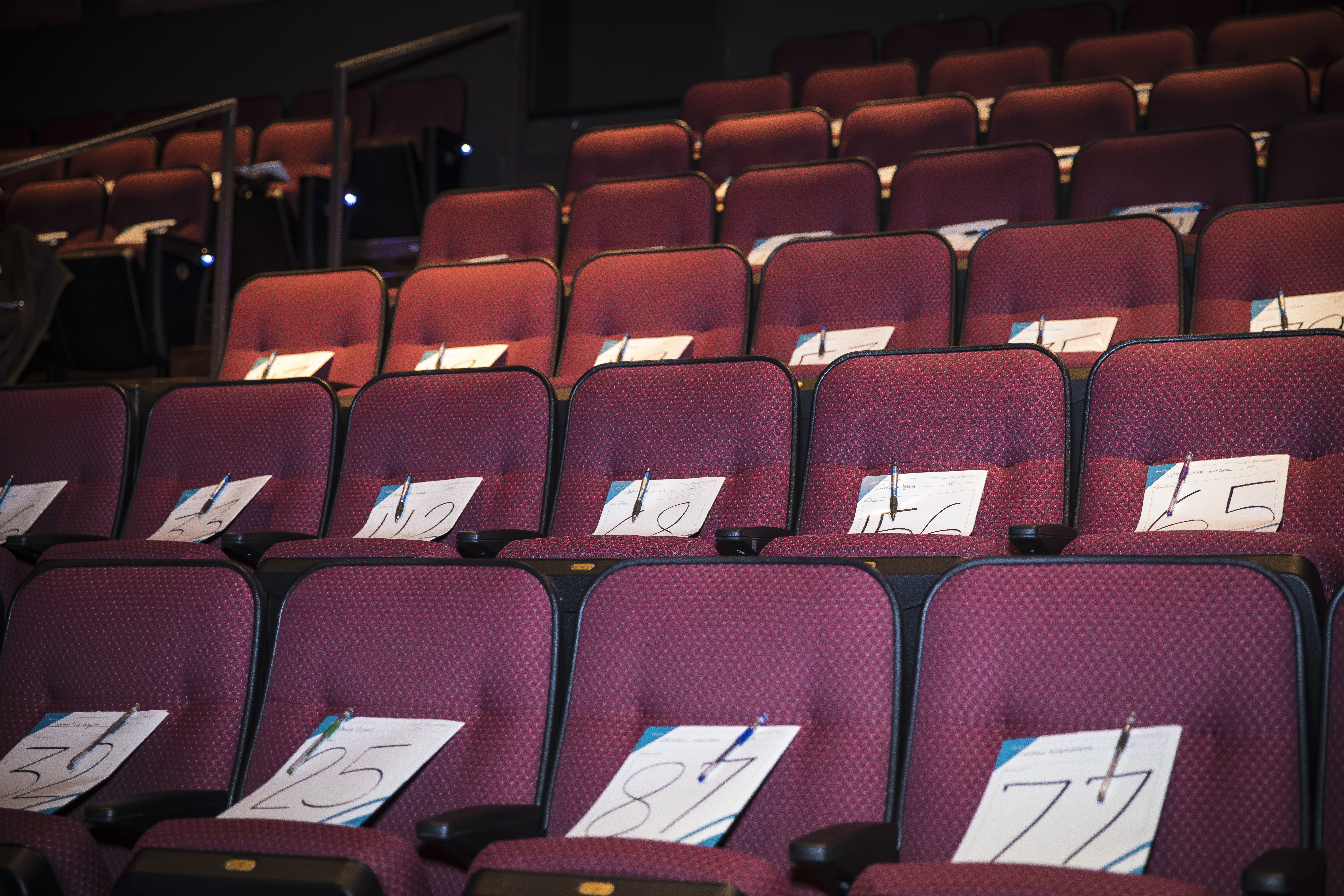

See Derecho on October 7 & 8

Reserve your seat now – it’s Pay What You Can! Click here to check out locations & dates.

About Derecho

In Northern Virginia, sisters Eugenia and Mercedes Silva are surrounded by old friends and lovers as Eugenia fights for endorsement on her primary campaign for a seat in the Virginia General Assembly, hoping to join the wave of women of color elected to public office. As a storm brews outside, the sisters must confront how traditional Latino family values conflict with an American definition of success that is always changing. An experimental play that explores how fragmented identity can tear you apart.

Wayne Paul Mattingly

Posted at 20:54h, 07 OctoberI hope I am available to see this work.. Initially interested to see how

traditional Latino family values conflict with a American definition…”